[Chenglish] Chunyun implies more than mass migration

- 2014-03-17

Epic traffic jams in many Chinese cities and in the country's capital city, Beijing, in particular, has been in the press for years. No matter if it is because of bad weather, road construction, school year commencement or weekend rush, even a trivial matter can virtually bring the municipal traffic to a halt, leaving tens of thousands of drivers stranded on the street. Journalists are already callous to endless complaints against these year-round scenarios and ironically have started to report on empty roads instead of routinised congestion. Together with uniform shutdown of government houses and private businesses, the bizarreness of city-wide smooth traffic marks the week-long Chinese New Year celebration – the height of Chunyun, when hundreds of millions of urban dwellers migrate back to their hometown for family reunions.

Dubbed as the largest scale of human migration in the world, Chunyun, literally translated as spring commute, refers to the massive exodus of Chinese people returning home from work or study elsewhere during the spring festival. It forms an annual stress test for the country's transportation system. The two biggest national "golden-week" holidays in China, namely the Lunar New Year and national day celebrations that each last for one week, are often compared to each other. Both of them give people enough time to travel to a more distant place, but it is Chunyun that evokes people's emotional bonds to their family and poses a near mandatory duty for all Chinese people to go home, regardless of how much they earn.

Of course, the well-off class can afford to go anywhere on either occasion, but for the giant army of lowly-paid migrant workers who have been consciously saving every penny that they pocketed, a sightseeing trip during the national day celebration seems too luxurious. They prefer to work overtime in this festive week of October and if the wallet allows, buy the cheapest train ticket to enjoy their family gathering once in a year. Even though they might barely have a place to stand on the train for their whole journey, let alone have a seat in an overcrowded carriage whose toilet is often stuffed with several passengers, all their tiredness and unhappiness becomes replaced by joy and laughter as soon as they return to their most familiar place.

Dictated by both the Chinese tradition and the overwhelming majority of the population heading back home, Chinese authorities set up the Chunyun mechanism two decades ago to cope with the national travel rush from January to February. Seven government departments in charge of Chunyun, including the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Transport, the newly-revamped National Railway Administration and the all-powerful National Development and Reform Commission, designated about 40 days for the travel season, required local governments to mobilise public transport vehicles at almost full capacity and deployed more than 180,000 police officers this year for inspection and patrol to facilitate the migration.

Despite the administrative effort to conduct ad hoc routes to accommodate more passengers and vehicular checks to ensure people's safety, Chunyun remains a headache, if not a cancer, for the officials to stand the pressure brought by the increasing passenger turnover, which was estimated to exceed 3.6 billion this year.

Coach riders embrace the biggest risk of encountering fatal accidents and air passengers have to fight for limited tickets that can be three times more expensive than the same tickets sold in other months. As to the railway system notorious for its suffocating population density and high charge over unswallowable food, I am sure you would bear all this "inhumane" stuff once you have known how tough it is to get a single ticket. Many people either have to spend hours and hours queuing at train stations only to find out there is no ticket left or pay more to buy a black-market one from the "yellow bull" – Chinese euphemism for scalpers. This explains why people cheered a couple of years ago, as they learnt they could also book a ticket online. But their excitement quickly shattered, because the fragile website quickly went paralysed, and buyers whose transactions failed had to wait for 30 minutes to submit a new order. As usual, people exhibited their creativity online, parodying a literary Chinese song with low-brow lyrics to voice out their disappointment.

Without any need to deal with Chunyun, I stayed in Hong Kong during the holiday and enjoyed watching the satirical song. However, life was much harder for the Chunyun horde without Internet literacy. Obviously they had to buy tickets in person and if their only channel was blocked, they could not even resonate with the song. Their urge to return home was so strong that news reports of "Chunyun motorcycle brigades" began to grab people's attention in recent years. Beyond my common understanding, they were willing to be totally exposed to the freezing temperature, occasional rainfalls and most dangerously, immense risks of losing their life on mountain roads that sometimes could not be even recognised by Global Positioning System, just to realise a simple dream of family reunion. I feel sympathetic towards them and hope they can help each other to reach their Utopia-like hometown peacefully and joyfully.

In short, the two-character Chinese word Chunyun is deeply ingrained in the 1.3 billion Chinese population, conveying their mixed emotions of longing for returning home, perseverance of making a living elsewhere, bitterness of the migration, and happiness of family reunion. I always cannot help shedding tears when glancing at media coverage in this period, no matter if it is about people's completion of their journey or a tragic accident that ruins a whole family. Putting aside the humanity aspect, we might easily blame the National Holiday Tourism Coordination Office, an official body affiliated to the country's State Council that decides the exact dates of public holidays.

Mass vocation is no one's vocation, and it is particularly true in the world's most populous nation where people simply shift the intra-city traffic jam to inter-city congestion. While certain holidays deserve to be kept, it is the time to encourage employers to give their staff the chance to enjoy more flexible holiday arrangements. Unlike in Hong Kong, where most companies clearly list out their annual leave policies before recruitment, many enterprises in mainland China are unlikely to overcome their bureaucracy to cater their employees. Worse still, with an aging population, the country's economy is slowing down, gradually driving the prospect of enhancing employee benefits into wishful thinking.

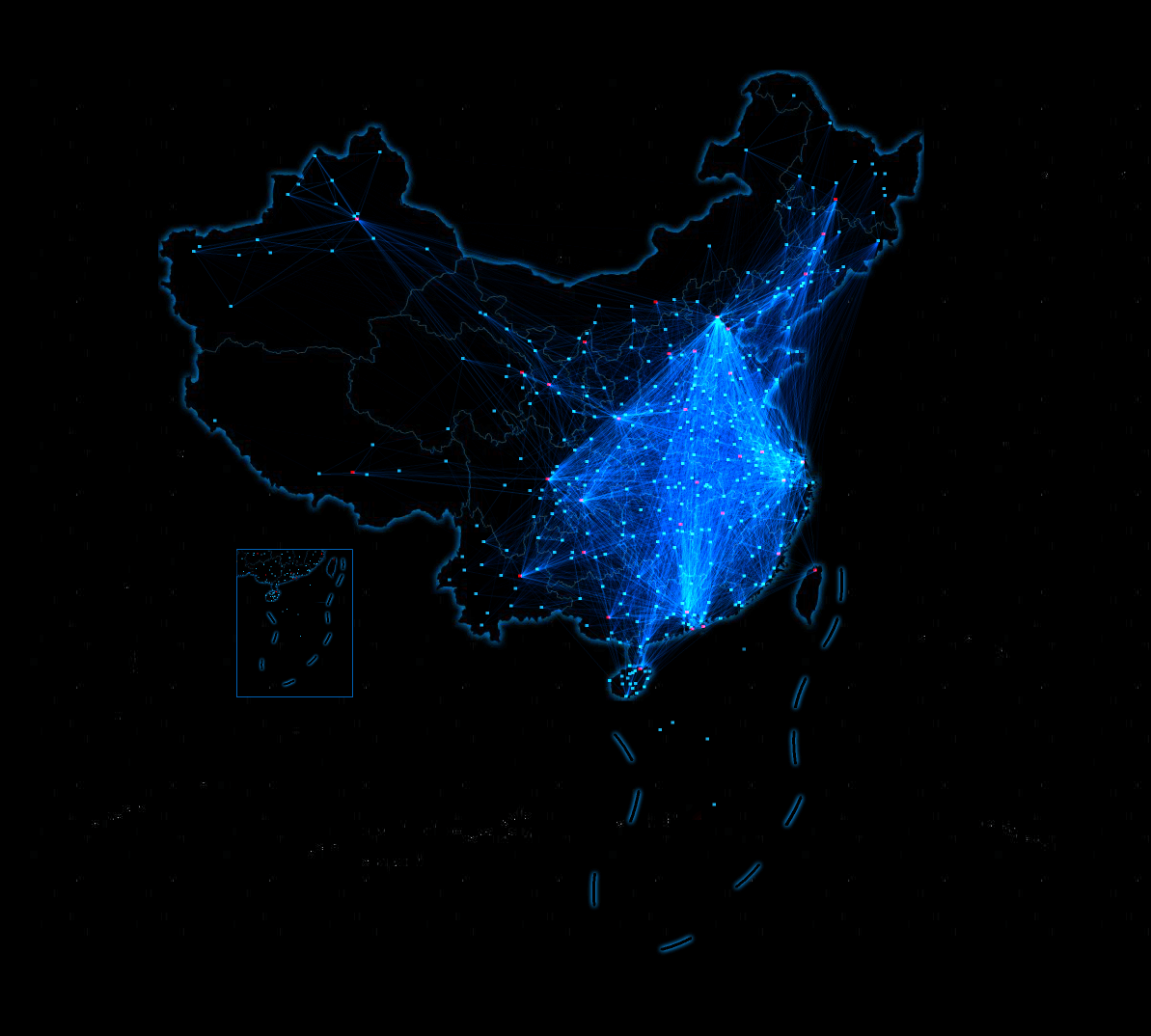

But how can Chunyun throw the country into traffic disorder every year? If people were working in their hometowns or somewhere nearby, they would not be involved in the travel rush, right? Yes, the logic sounds pretty simple and straight-forward, but the reality is not the case. A recent infographic made by China's search engine Baidu showed that traffic during Chunyun spanned the whole country, but it was extremely centred on the three first-tier cities, namely Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The process of urbanisation has turned the metropolises into magnets, attracting those migrant workers holding a traditional belief of "water flows downwards yet men climb upwards."

Regardless of their hard work, many people cannot manage to obtain a hukou in these cities - an invincible piece of household registration document that could bring benefits of various kinds ranging from social security, permit to buy car and flat, to children's education. Their weak living conditions and inferior social status do not drive them away, because they envision a more promising career there than what they could have enjoyed back in interior areas. In this sense, Chunyun accurately reflects China's uneven development, as well as people's constant struggle between economic pursuit for a better life and traditional obligation to kinship.

Having little confidence that the Chunyun dilemma could be solved in the near future, however, I still wish all these migrants a safe journey back and forth, as well as a bright future in the Year of the Horse.

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Drugged up, Settled down

[Cover Story]Young men ringing doorbells of sex workers

Comments