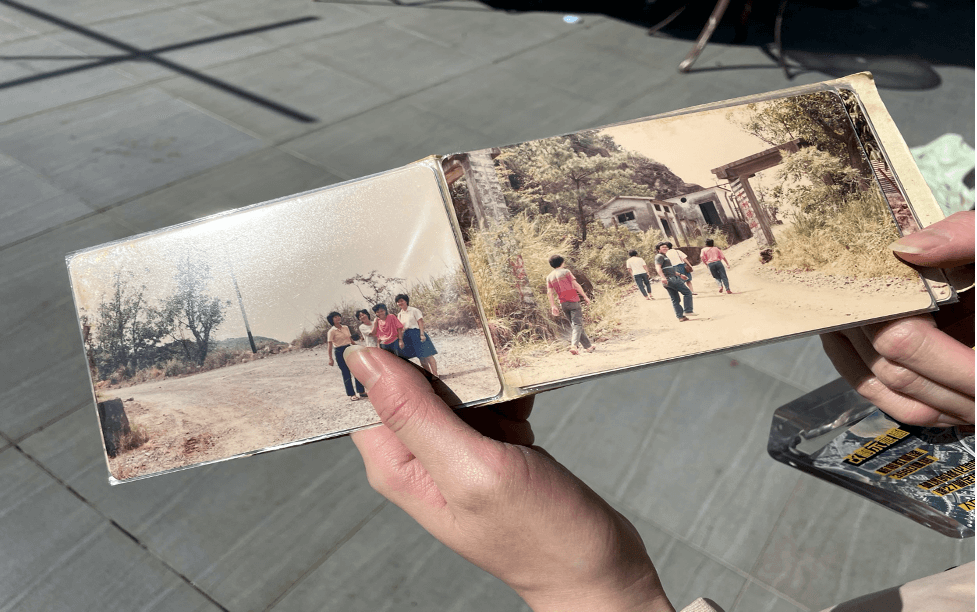

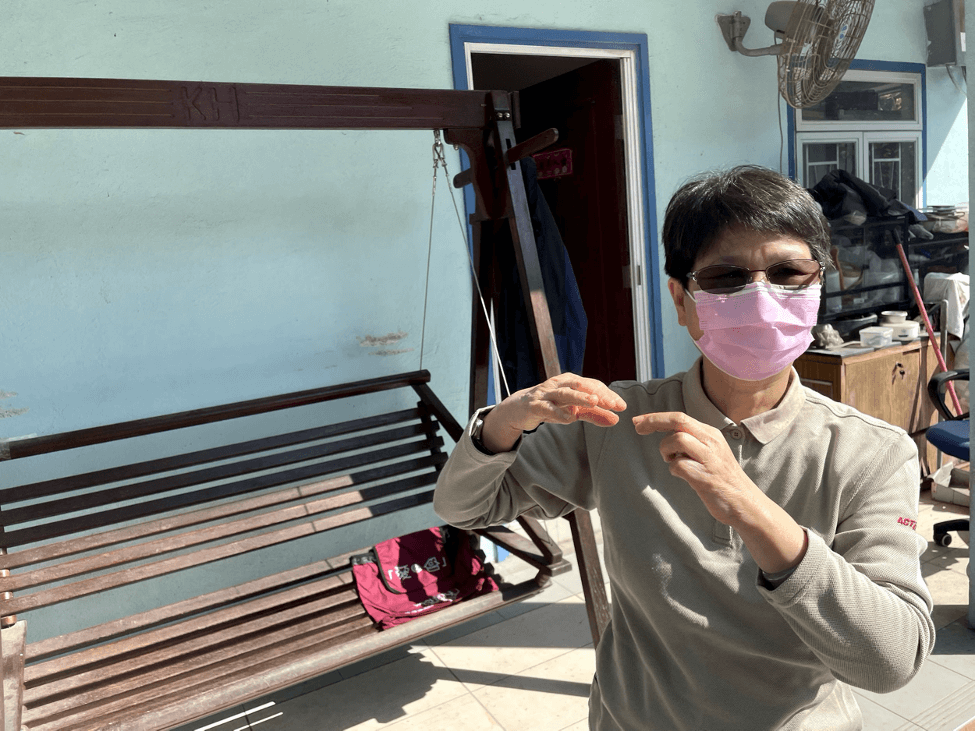

Wong Mei-fong, 55, still remembers her childhood summers in Pun Shan, a small village in the New Territories in Ma On Shan: catching shrimp in the rivers of the backyard garden, playing with mud with her neighbors who also helped them to renovate their house and playing hide-and-seek behind the old tree of the village temple.

These places will only be retained in memories if the amendment to the Ma On Shan Outline Zoning Plan passes.

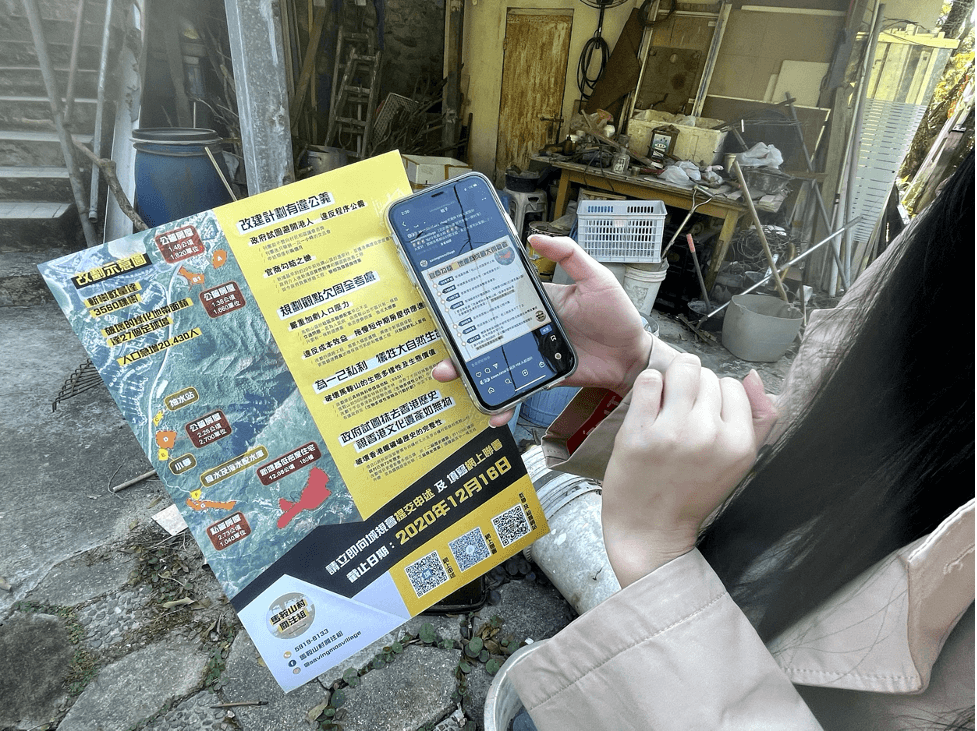

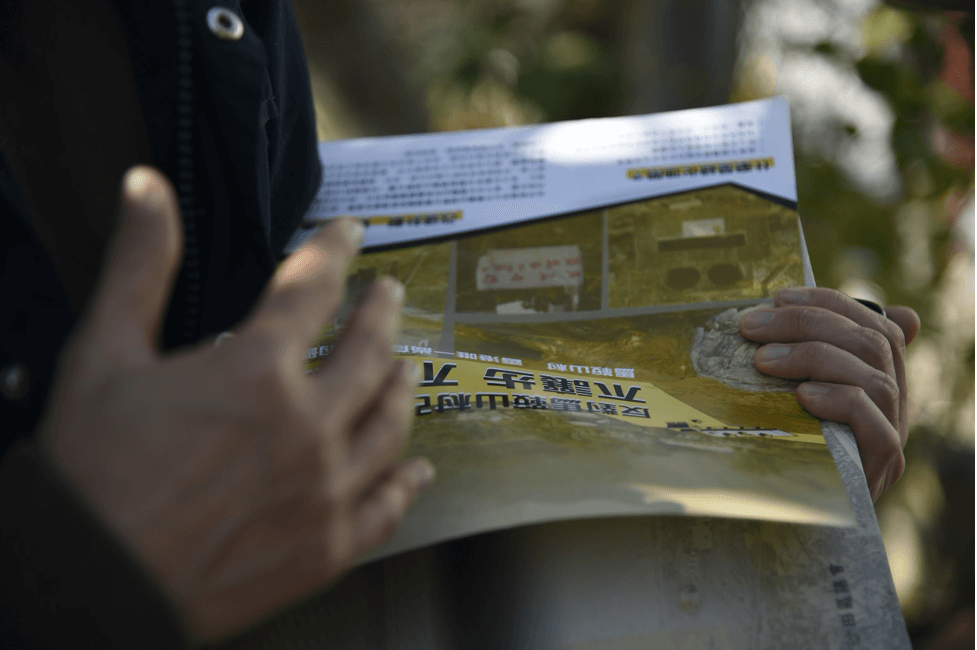

The Wong family represents three generations of villagers born and raised in this former iron ore mining village. Now, Pun Shan is marked for redevelopment in the amendment to Ma On Shan Outline Zoning Plan, originally approved in 2016 to develop 814 hectares of land. The new proposal will add 9.67 hectares from seven green belt lands, the size of approximately 27 football fields, and will cut around 3,560 trees, according to the villagers. The village land will be developed into a private estate and government, institution and community lands.

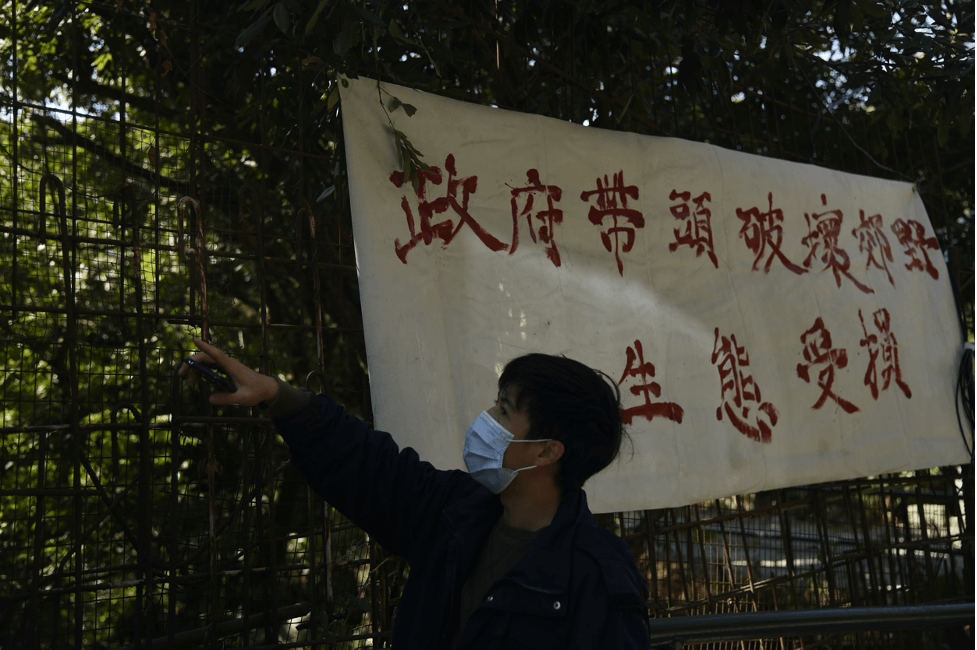

A group of villagers are actively protesting the amendment, working with district councillors and local green NGOs and setting up social media accounts to raise awareness. Villagers have held around 10 demonstrations to raise awareness of their plight.

“My parents don’t have much energy to protest and some of the elderlies are not familiar with social media, so we as the younger generation, take up this job to reach out to the public and attract more people to take part in preserving Pun Shan Village,” said Wong Yuk-hong, 29, the son of Ms Wong and the organizer of the rezoning plan protest.

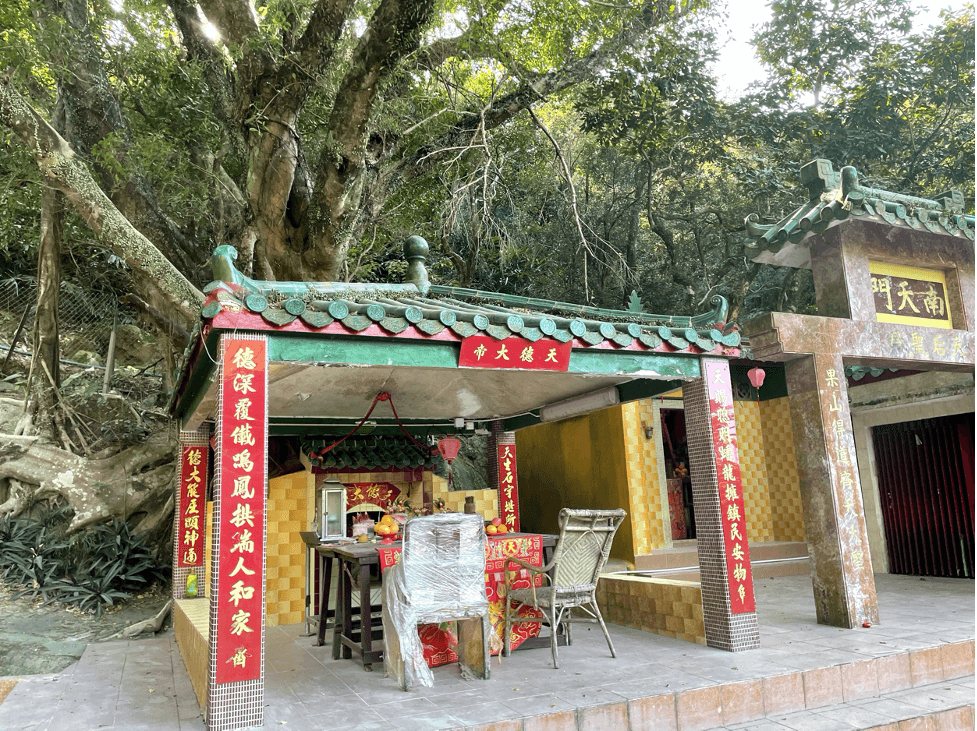

As one of the oldest mining villages in Ma On Shan, Pun Shan village witnessed the mining industry from its beginnings in 1906 to prosperity and finally to its closure in 1976. Every road, house and temple in the village was built by the first generation miners.

Mr Wong’s grandfather was in the first batch of Chiu Chow miners to explore Ma On Shan, and he built their family house with other miners in 1959, where Mr Wong’s grandmother still lives.

“All the villagers feel the same pity and sadness, as we want to preserve the historical memory of our ancestors,” said Mr Wong.

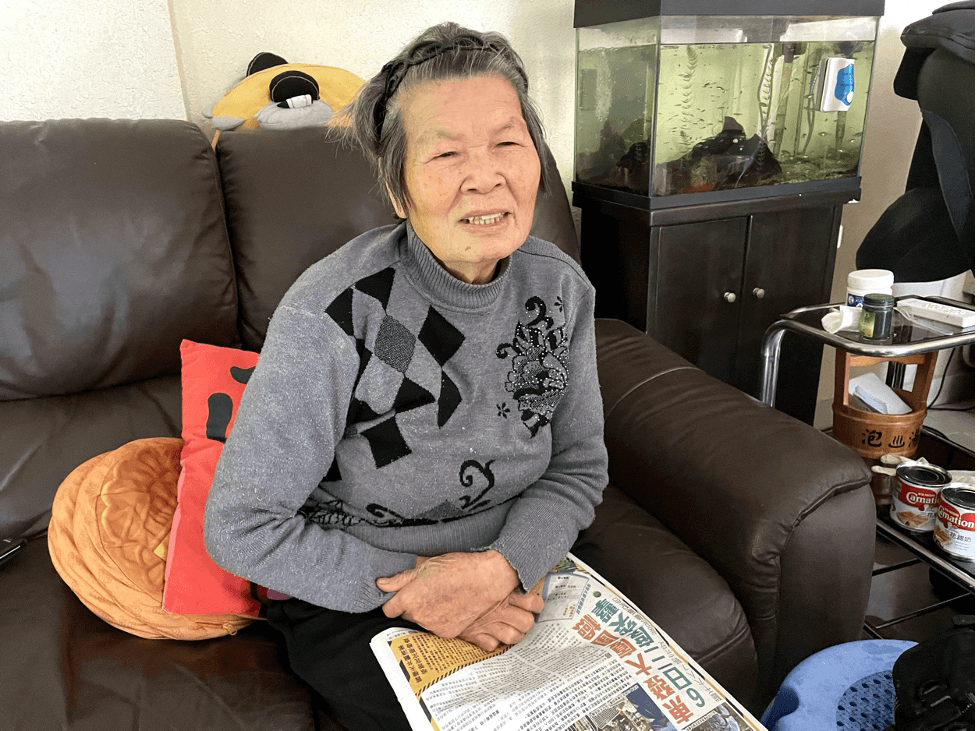

“I gave birth to my five children in the house,” said Lam Bik-ha, 81, Ms Wong’s mother and Mr Wong’s grandmother. Ms Lam has been living here for 61 years. When they arrived, Pun Shan village was nothing but a slope covered with plants.

“We built the village with our own hands. Although there were no nice materials, no one gave up,” said Ms Lam.

No money, no resources, dangerous terrain, these were not considered barriers as the villagers had a strong desire to build a home that belonged to them. Until now, Ms Lam is still impressed by the cooperation between households.

“During the daytime, men mined for a living while women raised pigs and farmed,” said Ms Lam.

A housewife, she spent most of her time taking care of her family and helping build the village. Women planted passion fruit trellises, banana trees and sewed handmade clothes to sell to local clothing factories. Today, villagers still raise pigs.

Ms Lam is still emotional when reminded of those days.

“We were poor, but we were happy and close to each other,” Ms Lam said.

Although many young villagers have moved out, the bond between the old neighbors remains.

“Despite the hard times, Pun Shan Village is still a wonderland to me,” said Ms Wong, adding that the Ma On Shan area was still isolated 40 years ago.

She went to high school in Shatin by boat every day.

“The government didn’t provide us any support during our hard times,” said Ms Wong, close to tears “When a typhoon no. 3 caused the boat to stop, I couldn’t go to school.”

Not until the 1980s, her nightmare of typhoons stopped as land reclamation was completed and the roads into the city were built.

“When living conditions become better, the government seeks to rezone our homeland,” Ms Wong added. As a nobody, she said, she has no power to fight against the government.

“As the first mine in Hong Kong, why can't the government leave this historical place to Hong Kong people?” said Ms Wong in a trembling voice.

Ma On Shan is not only a beautiful place for hiking, but is also a wonderful storage of Chiu Chow culture and the mining history of Hong Kong, she said,

“We have temples and mine culture. They are all symbols of ‘Hong Kong spirit’,” said Ms Wong.

The village, home to about 100 people now, is halfway up Ma On Shan mountain, surrounded by quiet and full of temples, old village houses, fish pools, vegetable gardens and pig pens. It’s a rare reminder of old Hong Kong.

Many residents still live in the past. “The Internet here is not strong enough, and most villagers still use mountain spring water,” said Mr Wong as he headed towards the mountain top.

The Chiu Chow temple at the top of the village is dedicated to three gods, the Earth God of Heaven, Chinese Sea Goddess and Monkey King.

“It is a holy place in our village,” said Mr Wong. “Our ancestors believed that the tree could protect the village's peace and safety. We all believe in that,” he said while repeatedly touching the ancient tree behind the temple.

“But now these might all be gone,” said Mr Wong.

Mr Wong said that the second round of protests and collection of signatures began on Jan. 30.

“We won’t allow our homeland to become a cold building block,” said Mr Wong.

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Privacy concerns drive people away from evening dine-in

Hong Kong strives to achieve carbon neutrality goal, long-term decarbonisation strategy expected mid-2021

Comments